|

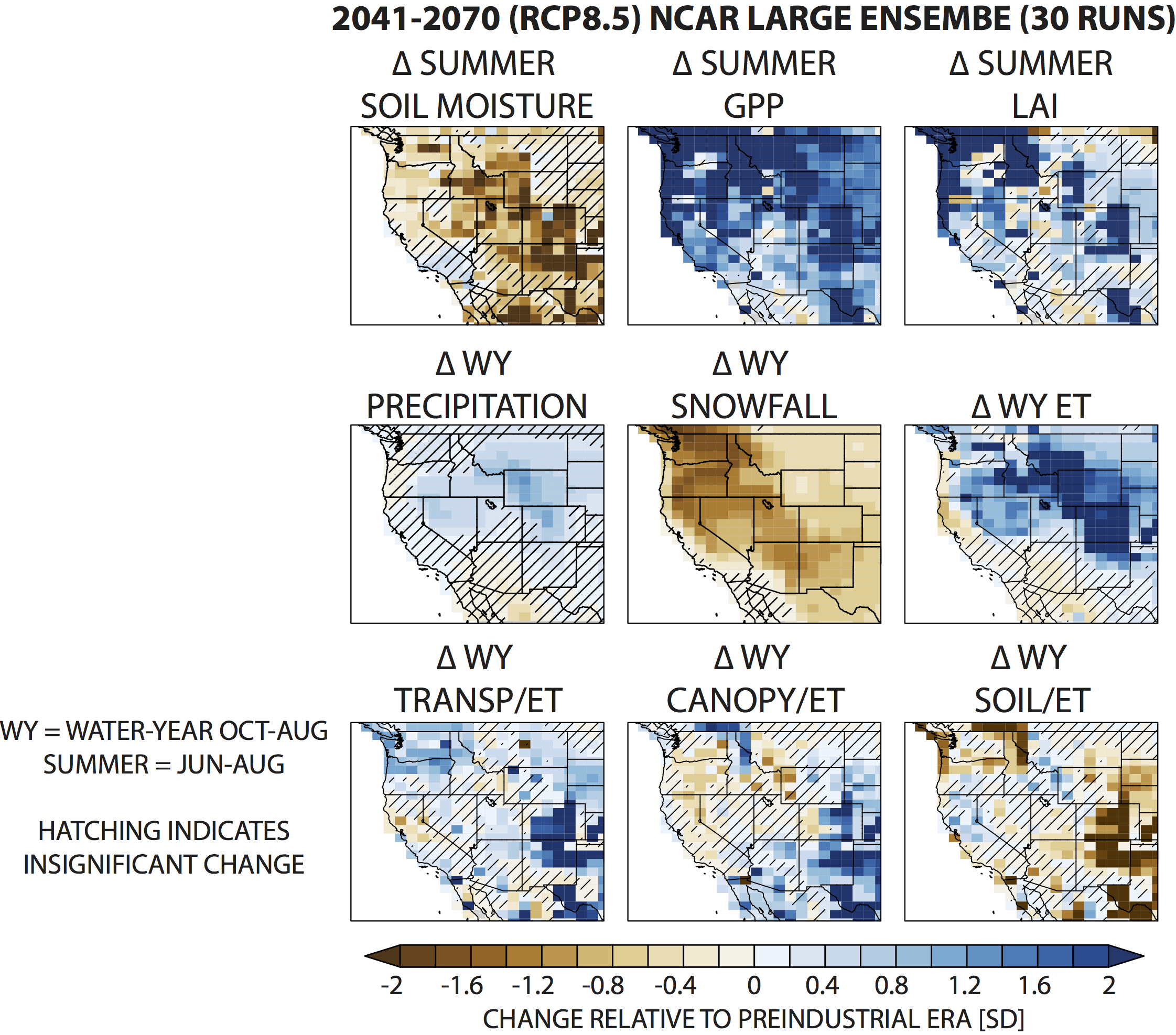

18. The curious case of projected 21st-century drying but greening in the American West - PDF Common measures of drought or surface drying are the Palmer Drought Severity Index - PDSI, an index based on a simple soil moisture balance model - or the soil moisture itself computed in land surface, climate and Earth System Models (ESMs). It is commonly assumed that a decline in PDSI or soil moisture indicates drought and, hence, water stress on vegetation. In this recent paper (Mankin et al. 2017) we discuss the curious cases that current generation Earth System Models project for the current century that, across most of the American West, while soil moisture declines the vegetation “health”, as measured by primary production or leaf area, increases. We refer to this as “drying but greening”. This is surprising in several ways. Rising CO2 in the atmosphere is expected to increase plant water use efficiency (WUE) as carbon uptake in photosynthesis can occur with less loss of water from stomata. However warming can also encourage phenological changes that raise productivity and leaf area and increase water use. In the ESMs the latter effect dominates and, despite increases in WUE, “greening” causes “drying” as higher evapotranspiration decreases soil moisture. While this is what the models do, we are not so sure that they are right. Some support comes from analysis of the Last Glacial Maximum as in Scheff et al. (2017). In that case paleo records of reduced vegetation can be reconciled with model simulations of greater soil moisture once the reduction of CO2 is accounted for. However a reduction of CO2 to below 200ppm is not the same in terms of impact on plants of an increase by a similar amount due to other limits on productivity and the ability of vapor pressure deficit to rise exponentially with temperature.

Figure 1: Here we show the ecohydrological response in the NCAR Large Ensemble for the middle of the current century. There is a widespread reduction in soil moisture at the same time as an increase in Gross Primary Productivity and Leaf Area Index. Also, this occurs even as precipitation increases away from the southwest. More water is lost to evapotranspiration (ET) with transpiration achieving most of that as opposed to changes in canopy or soil evaporation. In the model, vegetation is essentially driving a reduction in surface moisture and runoff (not shown), that is, in the water available for human use. Also, as of now, despite considerable effort, it is not clear how ecosystems are responding to the simultaneous increases in temperature and CO2 and changing precipitation. Recent trends are also confounded by natural decadal variability such as the widespread and persistent drought conditions that have dominated over the West since the 1997/98 El Niño. What the real response will be deeply matters. If ecosystems respond as the ESMs suggest then it could mean they reduce the water available in soils and rivers for use by humans for irrigation and water supply. How the entire eco-hydro-climatological system responds to human-induced changes in our planetary systems, and how this will impact that part of the water available to humans, is a huge current research challenge as this paper emphasizes. REFERENCES

|

EASM2: LINKING NEAR-TERM FUTURE CHANGES IN WEATHER AND HYDROCLIMATE IN WESTERN NORTH AMERICA TO ADAPTATION FOR ECOSYSTEM AND WATER MANAGEMENT EASM2: LINKING NEAR-TERM FUTURE CHANGES IN WEATHER AND HYDROCLIMATE IN WESTERN NORTH AMERICA TO ADAPTATION FOR ECOSYSTEM AND WATER MANAGEMENT | |

| Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University 61 Route 9W Palisades, NY 10964

| |

|

| |